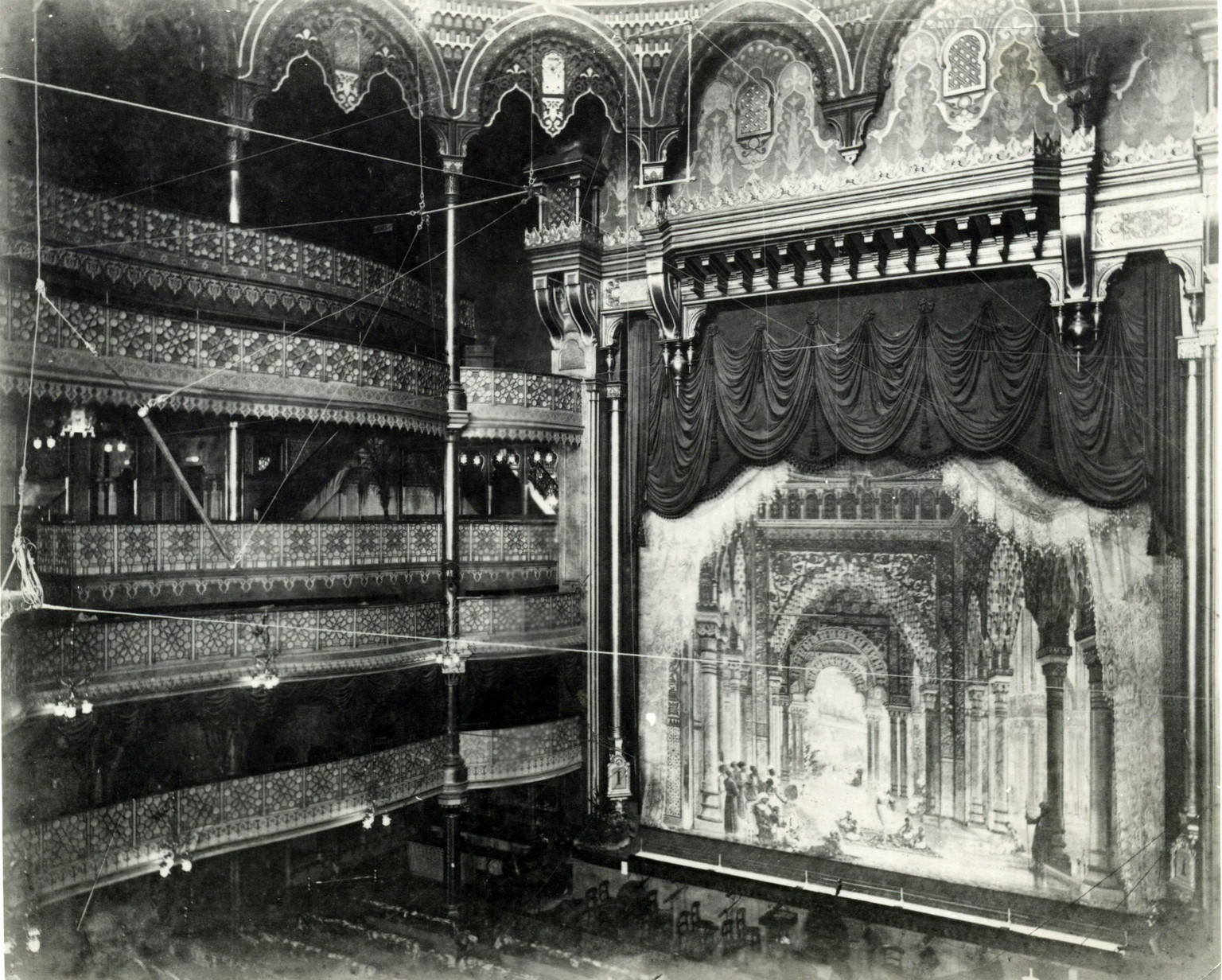

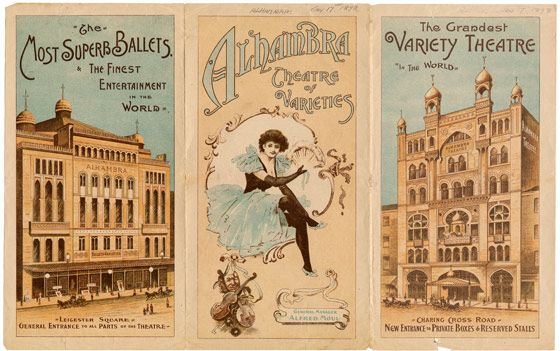

After the Lumière Cinématographe opened at the Empire Theatre of Varieties in March 1896, its neighbour in Leicester Square, the Alhambra, moved quickly to sign up Robert Paul, renaming his projector the ‘Animatographe’. Almost overnight this young electrical instrument maker found himself part of the programme at one of the key venues of Decadent London.

The audiences of Leicester Square’s music halls would have cared little which device was playing at their favourite theatre, apart from its novelty. What soon mattered was the actual subjects being shown as part of the rich programme of ballet, song and drama that catered for a surprisingly diverse audience at these vast halls. For many, they represented the fleshpots of depravity, hell-bent on ‘demoralising’ their audience. They were also known to cater for the West End’s large population of ‘ladies of the night’ and their wealthy clients. Which led to the Empire erecting a canvas screen to separate the sexes on its promenade, in response to Mrs Ormiston Chant’s morality campaign. On 3 November 1894, a group of military cadets from Sandhurst, led by the 19-year-old Winston Churchill, triumphantly tore down the screen, with Churchill proclaiming ‘Ladies of the Empire, I stand for Liberty’.

Nothing in the Lumière show at the Empire would have offended ‘prudes on the prowl’. But next door at the Alhambra, Paul’s Animatograph programme already included two films of the theatre’s own famous ballet troupe, celebrated by the poet, journalist, and self-styled ‘music hall aficionado’ Arthur Symons in his journal The Savoy. Symons defended his praise of ‘the charm of rouge on fragile cheeks’, describing in sensuous detail his delight in seeing the performers backstage, as well as from the front stalls ‘as the curtain falls on the last grouping [when] the front row applauds violently… and every man, as he applauds, is looking in a different direction’.

In May 1896, the Alhambra’s manager, Alfred Moul, realised that the Animatograph programme needed something fresh and perhaps more in keeping with the style of the theatre. He proposed to Paul that they ‘add interest to wonder’, as Paul later recalled, and make use of the theatre’s resources to stage a comic scene on the roof. The result was The Soldier’s Courtship, starring the Alhambra’s leading dancers, Fred Storey and Julie Seale, as lovebirds whose passionate tryst is disturbed by a large matron installing herself on their park bench. When they fail to dislodge her, the soldier tips over the bench and she retreats furiously, leaving the pair to return to their lovemaking.

The Soldier’s Courtship was immediately popular, hailed by the showman’s paper The Era as adding ‘humour’ to the animated pictures by means of ‘clever invention’. How successful it was could hardly be appreciated until 2010, when the Cineteca Nazionale in Rome co-ordinated a restoration of this pioneering film, drawing on material from various archives. Compared with Edison’s contemporary The Kiss, a rather tame moment from a play filmed in close-up, Paul’s three performers throw themselves into the action with style and commitment. And the production would have a lasting significance for Robert Paul, when eighteen months later he married the dancer who had played the ‘lady of mature years’, as described by The Era – Ellen Daws, padded up in her costume and just twenty-nine at the time.

There would be more ‘adult humour’ in another film made by Paul in August that year. 2 a.m. or The Husband’s Return was, like Edison’s Kiss, taken from a popular stage work of the day. In this case, it is the Parisian actor Paul Clerget, rolling drunk after a night out, who is coaxed into bed by his exasperated wife, played Ethel Ross-Selwicke. But it would be a mistake to judge the few brief extant films of this period solely on what we see. Contemporary audiences were capable of reading much more into them, especially in the novel darkened conditions needed for early film projection, unlike the normal theatre lighting.

A striking example of this comes in an 1897 story by the ultimate man-about-town George R. Sims, described in his Times obituary as ‘a highly successful playwright… a zealous social reformer, an expert criminologist, a connoisseur in good eating and drinking, in racing, in dogs, in boxing, and in all sorts of curious and out-of-the-way people and things’. ‘Our Detective Story’, published in The Referee, is narrated by a private detective who visits the Alhambra, then showing Paul’s series A Tour in Spain and Portugal, where he sees a former client and his wife. The detective’s brief had been to shadow the wife, suspected of adultery, in Madrid; and as they talk, the lights go down and the pictures begin. When they reach a scene in a Madrid park, both the husband and detective recognise the wife with another man. ‘Stay madam,’ the husband hisses, ‘I will see the end of this.’ The story ends ‘In Court’, where the divorce case is being heard, with the film as evidence of adultery. The idea that films could provide evidence of wrongdoing would be exploited often in the years to come, but this early example reveals a shrewd understanding of what Victorian imagination could bring to early film shows. Whether Paul’s Tour in Spain does include a kissing couple must remain a mystery, since all but one fragment of the film is lost – like 80% of Paul’s output.

Paul didn’t exactly’ run away with the circus’, but he had at least several years of backstage life around London’s music halls, racing from hall to hall every night by cab, and getting his ever-growing programme of films onto improvised screens. He soon hired projectionists, and built a studio in Muswell Hill in 1898. But while researching his somewhat mysterious life, I was surprised to discover from a family friend’s memoir that he and Ellen were the life and soul of parties at the Café Royal, notorious as ‘the haunt of Bohemian London’, with habitués that included Oscar Wilde, Aleister Crowley and Max Beerbohm. To learn that the Pauls often visited ‘that exuberant vista of gilding and crimson velvet set amid opposing mirrors and upholding caryatids’, as Beerbohm described it, gives an unexpected new perspective on their life.

Above: paintings of the Café Royal by Charles Ginner and William Orpen in the 1910s.

Above: paintings of the Café Royal by Charles Ginner and William Orpen in the 1910s.